Last Post: WW1 remembered

Union Matters November 11 2018 Amid the many commemorations and acts of remembrance taking place today (November 11) to mark the centenary of the end of the First World War, we here retell the largely forgotten story of the GPO’s unique role at the heart of the UK’s 1914-1918 war effort and the extraordinary contribution of a workforce that found itself on the front line in every possible sense…

Amid the many commemorations and acts of remembrance taking place today (November 11) to mark the centenary of the end of the First World War, we here retell the largely forgotten story of the GPO’s unique role at the heart of the UK’s 1914-1918 war effort and the extraordinary contribution of a workforce that found itself on the front line in every possible sense…

As the storm clouds of impending war gathered over Europe during the infamously hot and sultry summer of 1914, the day-to-day work of the British Post Office carried on as normal – servicing the insatiable letter-writing antics of a population for whom the post represented the only widely accessible form of communicating over distance.

Little did the 250,000-strong workforce of what was then the world’s largest employer know it, but the organisation they worked for and their very lives were about to be transformed. Most, after all, believed the then prevalent mass-delusion that the ‘war to end all wars’ would “all be over by Christmas”.

Within four years over 8,500 Post Office personnel would be dead and tens of thousands more injured, many permanently maimed. The names of those who perished still adorn the 300-plus memorials that were erected in almost every significant UK Post Office building shortly after the war.

In an age when the death of a single UK soldier on active service overseas makes national television news, the human cost of WW1 defies modern comprehension. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme alone, more than 60,000 British casualties were recorded, making July 1, 1916, the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army.

In an age when the death of a single UK soldier on active service overseas makes national television news, the human cost of WW1 defies modern comprehension. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme alone, more than 60,000 British casualties were recorded, making July 1, 1916, the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army.

Over a million British and Commonwealth forces died during the course of the First World War out of a total of around 10 million military personnel deaths – leaving profound and perhaps unanswerable questions as to how those in command could possibly have viewed the slaughter on all sides, typically for negligible tactical gain, as in any way ‘a price worth paying’.

What is certain, however, is that the carnage of the so called ‘Great War’ had a profound and lasting effect on UK society as a whole – and perhaps none more so than on the Post Office which, by virtue of its then pre-eminent position as the UK’s communications provider, found itself at the very epicentre of Britain’s war effort.

Contradictory expectations

The pursuit of war requires large numbers of recruits willing or conscripted to fight and, crucially, effective communications. In 1914 this stark reality immediately posed massive contradictory demands on the Post Office which, then a Government department with a predominantly male workforce, was inevitably expected to ‘do its bit’ encouraging employees to sign up for military service – just as the demands being placed on the post and fledgling telecommunications systems it provided were rocketing.

The volume of mail increased dramatically during the war years, rising from 700,000 items a day in 1914 to 13 million at its height.

In 1914 some areas in Britain had post delivered up to 12 times a day, but these deliveries were drastically reduced as a depleted workforce battled to cope with spiralling mail volumes. After the war the number of deliveries was never fully restored.

PO joins up

Despite the fact that every man ‘lost’ to the forces meant a resourcing headache for the Post Office, the organisation actively encouraged its staff to join the war effort – aided by the then general secretary of the Postmen’s Federation, George Stuart, who appeared on platforms across the country urging ‘every young man who is physically fit and capable of bearing arms to rise to the occasion’.

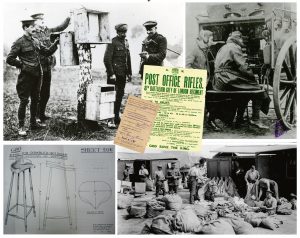

Over 75,000 men left their jobs to fight – 12,000 joining the PO’s own battalion, the Post Office Rifles. So many men were keen to enlist that a second battalion had to be created a month after war broke out.

The Post Office Rifles fought at Ypres, the Somme and Passchendaele and were awarded 145 decorations for gallantry, including a Victoria Cross (VC) awarded to Sgt Alfred Knight of Birmingham for putting his own life at risk to save others by leaving the relative safety of his trench and single-handedly charging a German machine gun post that was pinning a section of his men down.

Three other Post Office recruits serving in different battalions – Albert Gill, Henry Kelly and John Hogan – also received the VC.

While the Post Office Rifles was a fighting unit with no involvement in the day-to-day business of letter delivery to and from the trenches – a task conducted by the Army Post Office, which was also largely staffed by PO volunteers – one instance was recorded of an enterprising group of PO Rifles delivering letters from German PoWs to their comrades in the trench opposite by cutting slits in unappetising oversized carrots that no-one wanted to eat and hurling them over no man’s land!

Albeit heart-warming, this rare glimpse of humanity in the squalor of trench warfare was – just like the fabled instance of football being played in no man’s land on Christmas Day in 1914 – a brief interlude in a four-year nightmare of suffering, loss and random death.

Over 1,800 members of the Post Office Rifles were killed in action during the course of the war, and a further 4,000 – a third of the total – wounded.

Delivering for good and ill

While postal communications played a vital role in the war effort the Post Office also ran the UK’s then fledgling telecommunications system and was instrumental in setting up the crucial telephone system between headquarters and the front line.

Over 11,000 Post Office engineers made this possible throughout the war. Maintaining and repairing the system on the front line was fraught with danger, though no statistics exist as to the number who died.

Many soldiers had relatives and friends fighting in other units – and from December 1914 the Post Office ran a postal service that carried mail between units as well as cherished messages from loved-ones at home.

Writing and receiving letters and parcels were a vital part of sustaining morale amid the squalor and horror of trench life.

Back at home in the UK relatives and friends of soldiers on active service eagerly awaited messages from their loved ones. Inevitably good news for some was counterbalanced by the worst for others.

As the death toll mounted – and particularly after the major offensives – the task of mail delivery could be a harrowing one, with Post Office employees often being the first to get inklings of bad news that invariably hit communities in waves.

“News of people being killed or lost or captured was often relayed by telegram and the telegram inevitably became associated with bad news,” explains Chris Taft of the award-winning new Postal Museum in London.

“In WW1 the arrival of the messenger boy filled people with dread. It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like for these youngsters, some as young as 14. Sometimes the person answering the door would collapse or faint at the sight of them – sometimes they were asked to read the telegram because the person it was intended for couldn’t bring themselves to read it. Often it was the very worst news, effectively relayed by children.”

Few of the personal accounts held by the Postal Museum better illustrate the emotional rollercoaster that correspondence to and from the front line represented than the tragic story of Harry Brown – an Eastbourne postal worker serving in the PO Rifles. After being sent to France Harry regularly corresponded with his mother until one of her letters was returned unread, with the notification that he had gone missing in action.

Distraught and desperate for more information she wrote to the British Red Cross, which managed casualty lists – initially receiving the reply that Harry was presumed to have died in battle. A short while later, however, she received a letter from Harry himself, saying he was okay but being held in a PoW camp in Germany. During the course of their subsequent correspondence Harry fell seriously ill, though appeared to be making a recovery just before the end of the war. In a tragic twist of fate his mother received the bombshell notification that Harry had died following a sudden deterioration of his condition just days after the Armistice.

Harbinger of change

Looking back on the horrors of WW1 it seems perverse to even contemplate that anything positive could have come out of a tragedy of such hideous proportions. Profound shocks to the national system, however, sometimes force progressive change that otherwise may not have happened so quickly.

Frequently cited examples from WW1 include the role of women in a society that had previously largely denied them the recognition and rights enjoyed by men and a widespread questioning of the rigid pre-war class system stemming from both the belief that ‘lions had been led by donkeys’ and the shared experience of suffering and loss.

Many argue that the very concept of the ‘Home Front’ acted as a great social leveller, acting as a stimulus to wider social reform after the Armistice. Even during the war years the first tentative steps were made to address the grinding poverty and associated ill health of the poorest in society – though positive developments like the Rent Acts can be attributed, with some justification, to an establishment desperate to stave off outright revolt at home and to ensure a continuing supply of healthier ‘cannon fodder’ as the war wore on.

By 1918, however, the bargaining hand held by trade unions had been considerably strengthened by the key role they played in negotiating the pay and conditions of workers involved in essential wartime production.

There’s also no doubt that the massive contribution of the female workforce to the Home Front helped provide the catalyst for the Reform Act of July 1918 which, following the pre-war vilification of the Suffragettes, finally secured the vote for women over the age of 30.

Within the Post Office the number of women employed in what had previously been an almost entirely male bastion rose from only around 2,000 in 1914 to 35,000 by 1918.

“In the early days of the war it was considered there were only a limited number of jobs that women could be asked to do – including sorting and things like the repair of damaged parcels and letters – but as the war progressed and women demonstrated they were perfectly capable of doing a wide range of duties they were given more and more to do, including deliveries,” explains Chris Taft.

“One job that was held back a long time, however, was that of opening letters that couldn’t be delivered because the recipient had been killed, because at the time it was felt that would be too upsetting for a woman. Gradually, however, that was opened up to women as well.”

The change was not without resistance. Historian Duncan Barrett recounts the struggle of a woman in Dorchester to overcome prejudice from both male colleagues and the public to become ‘head postman’ of a local post office – a development that resulted in a flurry of protest letters in the local press from customers saying they didn’t like having to deal with a woman at the PO counter and that she ‘couldn’t possibly be doing the job properly’ – even though she demonstrably was.

Despite considerable resistance, however, the ‘gender bar’ was broken. Even though most of the Post Office’s female wartime recruits were on temporary contracts, and many lost their jobs as male former post holders – who had always been promised their jobs back on demobilisation – returned to work, the number of women employees never again fell to pre-war levels.

Another progressive sea change that was effectively ‘forced’ on the Post Office – in part by its former pledge to staff enlisting in to the military that a job would be awaiting them on their return from war – involved its attitude towards disability.

With thousands who had suffered debilitating wounds determined to take the company at its word, a debate had been raging for some time about the proportion of disabled employees the business could sustain and the roles they could conduct.

Postal Museum archivist Helen Dafter concedes that much of the language of that debate is highly politically incorrect by today’s standards, as demonstrated by a report of the Post Office’s Committee on the Employment of Disabled Ex-Soldiers which read: ‘The way has, to some extent, been paved for the employment of disabled men by the employment of women in far larger numbers than we have suggested in the case of disabled men’.

“This equating of disabled men to able-bodied women seems to have been quite acceptable at the time, despite how offensive it sounds to both parties in modern society,” Helen admits – but the fact remains that, in the context of the time, a

Rubicon had been crossed.

- This feature first appeared in the September/October 2014 issue of The Voice and received a special commendation in the 2015 TUC Communications Awards