Big step towards justice for working-class heroes of the 70s

Union Matters May 23 2019A long-running campaign to win justice for trade unionists wrongly prosecuted back in the 1970s took a major step forward this month, with a key legal development that reopens the possibility of quashing the convictions of the Shrewsbury 24.

The prosecuted men were all building workers who had taken part in the national strike in the sector back in 1972, when militant picketing around the country’s construction sites had been the key factor in winning unprecedented pay rises and advances in other terms and conditions.

Des Warren addressing building workers during the 1972 strike

Photo used with permission of the Shrewsbury 24 Campai

Six of them were jailed – Des Warren, Eric ‘Ricky’ Tomlinson, John Mckinsie Jones, Arthur Murray, Mike Pierce and Bernard Williams receiving sentences from six months to three years – while the others were all handed suspended terms.

Explaining this month’s latest legal development, Eileen Turnbull, the secretary of the Shrewsbury 24 Campaign, said: “At our judicial review that was heard at the Administrative Court in Birmingham, the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC), half-way through our QC’s submission, agreed to withdraw their 2017 decision not to refer the convictions of the pickets to the Court of Appeal.

“This is a magnificent victory for the pickets and reopens the possibility of quashing the convictions of the Shrewsbury 24.

“The campaign is absolutely delighted and relieved and this is a testament to all our hard work and the support of the labour movement.”

In a personal message to our general secretary Dave Ward, Eileen said that the campaign was grateful “particularly yourself and your members through your support and encouragement,” referring to the longstanding backing that the CWU has expressed for the Shrewsbury 24 Campaign.

Dave says that this legal victory is “great news” and he praised the “passion, commitment and a determination” of Eileen and the campaign team.

“However long it takes, our movement will keep fighting for justice.”

The year 1972 remains one of the most successful and celebrated 12 months in the history of our movement, when a well-organised, confident and militant working-class set a post-WWII record of 23 million strike days and won a string of victories.

But while the miners’ and dockers’ strikes – ‘Saltley Gate’ and ‘Pentonville’ etc – dominate the collective folk memories, that year’s building workers’ strike is less well known by comparison, although it was, in many ways, an even greater achievement.

Even in those heavily unionised times, when closed shops were the rule in most of our industries, only around one-third of construction workers belonged to trade unions – the largest in that sector being UCATT, although both the GMWU (today’s GMB) and the T&GWU (currently part of Unite) also had building workers’ sections, as did furniture trades union FTAT (now within the GMB).

The four unions formed the National Joint Council for the Building Industry (NJC) and submitted an ambitious claim for a substantial wage increase and a shorter working week.

The National Federation of Building Employers (NFBTE), rejected the NJC claim and the strike was on, beginning in May of that year and being settled in mid-September, when the employers conceded pay rises of £5 and £6 per week – significant increases at a time when the ‘going rate’ in construction was around £20 per week.

During the strike, rank and file building workers had adopted the ‘flying picket’ tactics – pioneered by the miners earlier that year – visiting non-striking sites and persuading them to down tools, actions which were highly effective in spreading the strike and a major factor in its success.

But, after the dispute had been settled, the big building companies and the NFBTE lobbied the then Conservative Government for action against the strikers – particularly the ‘flying pickets’ – who had inflicted such a humiliating defeat on them.

Industry bosses collated information on the picketing actions and handed a detailed dossier over to the then Home Secretary Robert Carr, who instructed police chiefs to investigate, in particular, picketing of building sites in the Shrewsbury area.

In three separate trials in 1973 and 1974, the 24 men were convicted on charges including ‘conspiracy’ – a charge under an 1875 Act of Parliament – ‘unlawful’ assembly’ and ‘affray’ – despite no evidence of any violent acts or of any criminal damage being presented.

And the only evidence of ‘conspiracy’ that was offered by the prosecution was that a meeting took place of the building workers’ strike committee for the area, which planned the picketing actions.

In court, speaking from the dock just before he was sentenced to three years imprisonment, UCATT shop steward Des Warren firmly denied the accusations against him and his comrades, telling the judge: “The conspiracy was between the government, the employers and the police.

“When was the decision taken to proceed? What instructions were issued to the police, and by whom?” he demanded, adding: “There’s your conspiracy.”

He continued to fight for justice from his jail cell, refusing to wear prison uniform and demanding ‘political prisoner’ status – protests that led to Warren, a Communist Party member as well as a trade union activist, being administered liquid tranquilliser drugs.

After his release from prison, he was blacklisted and unable to find work in his trade – he was a skilled steel fixer.

Warren also developed symptoms similar to Parkinson’s Disease, which derived from his ill-treatment while in jail – experiences which he wrote about in his book The Key To My Cell – and he died at the age of 66 in 2004.

Ricky Tomlinson – who became a well-known actor in the 1980s and 1990s and remains a public figure today – received a two-year sentence, which was the second-longest sentence of the Shrewsbury pickets. He has continued to campaign to clear his comrade’s name, as well as his own and those of all the other wrongly convicted men.

Eileen says that “Warren’s premature death brought together a group of North West trade unionists to campaign to clear the pickets’ names.”

The application to the Criminal Cases Review Commission to quash all 24 convictions was submitted in 2012 “by 10 of the pickets, and also by Andy Warren on behalf of his father,” she continues, explaining that, in order for a conviction to be overturned, the CCRC must first agree to refer the case to the Court of Appeal.

And this latest development that she and her fellow campaigners are so pleased about is the campaign’s successful challenge to the CCRC’s 2017 decision to turn down their application.

Dave Ward says that he is “extremely proud to express our full and 100 per cent solidarity to this campaign from the CWU.

“These 24 men were working-class heroes – each and every one of them.

“They fought hard for decent pay, better conditions, and dignity and safety at work and they won, which was why the attack on them by the employers and their political party, the Tories, was so vicious.

“Never forget the late Des Warren’s words from the dock: ‘The conspiracy was between the government, the employers and the police.’

“Warren was right, and justice is now a little bit closer.”

Further information:

More about the 1972 strike, the trials and the campaign: www.shrewsbury24campaign.org.uk

Des Warren’s 1982 book Key To My Cell is available from the Campaign: https://www.shrewsbury24campaign.org.uk/how-to-support-us/#merchandise

Kevin Maguire’s and Ricky Tomlinson’s 2004 Des Warren obituary: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2004/may/01/guardianobituaries.politics

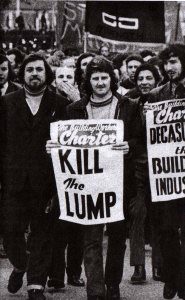

Rick Tomlinson and Des Warren on a demonstration. The ‘lump’ referred in the placard was the term used for the bogus self-employment of the day.

Photo used with permission of the Shrewsbury 24 Campaign