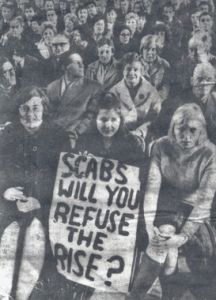

1971 Postal & Telecommunications Members’ Struggle & Strike

By Sean Ryan, CWU Retired Member

Our union’s history is rich and varied. However, as with most things in life, the tides of time tend to erase the memories and potentially diminish the sacrifice and courage of our members in years gone by. None more so than the historic struggles of members who took part in the first Post Office official national strike in 1971.

In 2021 we celebrate the 50th anniversary of this titanic battle, waged as it was, at the time, against a Government who hated the concept of public ownership of the postal and telecommunications sector, (sound familiar?) and was determined to drive down pay and conditions of its workforce, which at that time numbered almost 230,000.

From my perspective, and in talking to heroes involved in that campaign, I believe that one of the major failings of both the then UPW executive, (and some prominent activists) and the Government was that they all simply failed to read the signs of increasing resentment of in-work poverty, and long, long hours that members of all grades were expected to perform, in return for employment in the Post Office and to attain a living wage.

The situation was untenable. Members and their families had heard enough, worked enough, suffered poverty pay for long enough. It was time to stand up and fight for a fair share and they were in the mood to fight long and hard to achieve it. And so, at the spring conference in 1970, delegates mandated the union to achieve several pay-related “no strings” attached awards, including a 15 per cent straight pay increase.

In talking to heroes of that time, I am reminded that many hard-line activists felt they were not being taken seriously, and that they were simply paid lip service. I cannot of course, substantiate that – others involved, upon reading this, may or may not, confirm this – but it may account for what some believed, was a strike at the wrong time, without proper planning, and without the financial support in place that strikers would require in a dispute that was inevitably going to be lengthy.

The reader may also wish to reflect on the fact that this strike became, at that time, the longest, and the best supported (nearly 90 per cent of UPW balloted membership initially took strike action) and the most widespread UK strike since 1926.

Additionally, whilst members were understandably unhappy (to put it mildly) with the eventual outcome of the strike, it needs to be remembered that, as a consequence, what followed were above-inflation pay increases in the ensuing years and a major climb down by the Tory Government on anti-trade union laws. primarily attacking at that time the concept of the “closed shop.” This, coupled with a board of inquiry into pay and conditions of Post Office staff was seen as a positive step forward.

This, of course, was given scant regard by many members who saw any “gains” as minimal and were, for many years after, in unforgiving mood.

This, however, should not overshadow the efforts of so many members and activists whose individual and collective sacrifices enabled the UPW, and subsequently the UCW and present day CWU, to be feared and respected in equal measure by both the employer and governments of the day.

Whilst it can be reasoned that the 1971 strike fell on some of its initial aims, the legacy it created became the cornerstone of the principle of recognition that the union represents not only the views and aspirations of the membership, but that it demands from employers and governments levels of consultation and agreements that are unquestionably the envy of every trade union big or small in the UK.

This could only have been achieved, and built upon, because of the selflessness of activists whose personal sacrifices during that strike, should, and must be always remembered.

One such hero of that time was a late friend of mine, Ron Brown – I relate for the reader his recall of the strike – and who, in later years became a mentor, and long-time comrade of mine.

Ron was someone who sought no personal attention, save supporting and encouraging those who wished to serve the union more fully.

A very reserved man, Ron had firm principles, but did not, despite his demeanour, suffer fools gladly. Having a wicked and dry turn of phrase, he had no time for those who chose the union path for self-advancement, referring to them as “chancers and gobshites”. It was only recently during conversations about what we always termed “the strike” that he told me of what he termed “duty” during and after the 1971 strike.

He was an extremely shy man, the opposite of the public perception of a union official, married with three very young children when the strike commenced, he volunteered to do picket duty. Typically Ron, as a lay member at the time, spoke to the committee and it was agreed that he would act as “picket master” and try to formulise picket attendance where possible.

An added difficulty was that he had recently moved and this involved close to two hours of travel subject to the travel contingencies of the time. Additionally, cost was a factor, he could ill afford the daily commute and so, typically declining an offer from the committee to meet some of the travel cost, he approached the landlord of the Penny Black public house (as all good post persons would!), who agreed to let the committee have use of a phone and a room upstairs (which I, and others used as strike HQ for many years after).

The landlord provided blankets for him to sleep on the floor and sandwiches every morning, and Ron stayed there for the entire duration of the strike including weekends. Sometimes, as he remarks, it became a challenge trying to man two or three gates at a time, but he said he “just got on with it.”

He then became the focal point for information to members seeking updates on the strike. He attended with others, the weekly meetings at either Hyde Park or Friends House Meeting Hall in the Euston Road, walking as he did, to either venue, in all weathers.

Ron told of how his wife, Joyce, contacted him in a state of panic, as constant hand delivered letters from the bank were arriving at the door. The manager had summoned him to a meeting, expressing concern that several mortgage payments had not been met, despite several reminders.

He chose to ignore these, not through spite or arrogance – he was just frightened to be faced with being told to return to work or lose the family home. The following week (Week Five of the strike) was when his worst fears were realised. The bank wrote to say it was foreclosing on the property and that Ron had incurred bank charges running into several hundred pounds.

Ron met the bank manager and, although sympathetic, the manager informed him that steps would be taken to foreclose on the property and that before this took place, the bank was required to inform him of this formally and in writing by registered post for which he would be required to sign for.

By a delicious irony, Ron did not receive that letter because of the strike and, in a second stroke of good fortune, the strike was called off at the very point that the bank had lost patience and was about to revert to the courts for recovery.

I asked Ron recently what he would have done had things gone the other way. He said his wife would have supported him no matter what, and that he would have hoped to have had the courage to have stayed out, regardless of the threat.

I wonder how many of us would have had the courage to arrive at the same conclusion.

He rarely mentioned his role in the strike, simply saying, like others I have spoken too, that they were led by those wiser voices, both from other offices nationally, and of course in the London area, at the London District Council meetings and felt a certain pride that they had stood and once sat amongst them.

There was a deep sadness as I wrote of this courageous and unassuming man, when I received a call from his son John to say Ron had become victim to Covid and had passed away last December. I am deeply sorry. He was a special comrade and a kind human being. His family had requested that I record his activities and his efforts during the strike and I am proud to do so, but even prouder to record his achievements and sacrifice that epitomised that of thousands of postal workers during that dispute and since.

These former members and activists and the ever-smaller number who are still active in the union today epitomise the spirit of the time. The bravery of men and women like them deserve to be mentioned as heroes because heroes they were, and are.

We can only hope to emulate them in the struggles to come.

Finally, I leave you with the following words from Tom Jackson who, regardless of your view of him, led this union on members’ instruction, through what was at that time, the longest-running national strike since 1926.

I hope that in time, we may judge him more fairly than in the past, I fully understand the hardship and bitterness that the 1971 strike caused – God knows, like every branch secretary after that time, I was reminded of that dispute as soon as I wanted to “deliver” something other than the mail for many years after!

So, in ending, let Tom Jackson have the final word – this, his address, laced with bitterness to the TUC General Congress at the conclusion of the dispute.

“This brings me to the worst feature of British trade unionism. I have no doubt that it will be possible to weld together an army of the weak. But will the industrially strong sink their identity into such an alliance? Or will the prosecution of power-backed, sectional, self-interest be more attractive? The TUC is no stronger than the unions allow it to be. We must learn the lesson that, without a united movement, only a few of us can make advances. Some of us have learned this the hard way.”

Solidarity,

Sean Ryan,

Retired Member

Proud to have served in the finest, and one of the only, remaining trade unions, that dedicates itself to the defence of its members, and to the service of citizens in the UK, not merely by words or deeds, but when necessary, by individual and collective action, regardless of the sacrifice, regardless of the task, and regardless of the forces reigned against us. SR